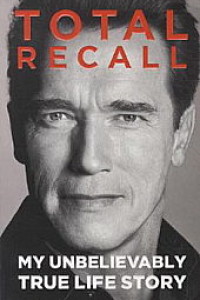

Total Recall. My Unbelievably True Life Story, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012, 646 pages.

For 35 years now I have closely followed the life of Arnold Schwarzenegger, and I probably read every biography of his that has ever been written. There is no other living celebrity that has impressed me quite as deeply. Predictably, it was with considerable excitement that I read the 646 pages of the autobiography that came out this year. I was literally clinging to words – and decided to honour the book with a more exhaustive review than I would normally write. I have penned several thousand book reviews in my time, but this one must be the most detailed ever:

Schwarzenegger grew up in a small Austrian village, the son of a police officer. In his teens, he developed an enthusiasm for two things – bodybuilding and the United States. Early on, he set himself the goal of becoming the most famous bodybuilder in the world. Afterwards he would go for a film career in Hollywood. People ridiculed him, imagining that a bit part in a cheap iron-pumping flick would be the best he could hope to achieve. Yet Schwarzenegger achieved his goals here as there, becoming one of Hollywood’s highest-earning actors. He also toyed with the idea of going into politics early in his life – and was eventually elected (and re-elected) as Governor of California, the world’s eighth-largest economy. By the way, he made many millions as a real estate developer before he became rich as a film actor. The money he earned in bodybuilding and in the film business he always invested in real estate project developments.

His book is about the unlimited superiority of the human mind, which far surpasses physical strength. A case in point, he tells the following story he witnessed with his friend and training mate Franco Colombo: “One afternoon … we were taking turns doing squats at Gold’s Gym in California. I did six reps with 500 pounds. Even though Franco was stronger than me in the squat, he did only four reps and put the bar back. ‘I’m so tired’ he said. Just then I saw a couple of girls from the beach come into the gym and went over to say hallo. Then I came back and told Franco: ‘They don’t believe you can squat five hundred pounds.’ I knew how much he loved showing off, especially when there were girls around. ‘I’m gonna show them. Watch this.’ He picked up the 500 pounds and did ten reps. He made it look easy. This was the same body that had been too tired ten minutes before. His thighs were probably screaming ‘What the fuck?’. So what had changed? The mind” (p. 68).

There are five reasons that explain the success of Schwarzenegger:

- He always set very high, sheer unattainable goals.

- He recognised the enormous significance of PR – he is and remains a PR genius.

- He had the courage to be different than the rest, and mastered the art of carefully calibrated provocation.

- He always had a tremendous passion for learning new things.

- He combined extreme self-confidence with the ability to unsparing self-criticism.

Even in his early years as a bodybuilder, he learned the art of marketing himself. He recounts how thrilled he was by the idea of his promoter Albert Busek to market his success at the Mr. Universe pageant (which was actually something that no one outside the rather small body builder scene cared about): Busek encouraged Arnold to walk down a high-street pedestrian zone in Munich in his posing outfit on a cold day. Then he called the newspapers: “You remember Schwarzenegger who won the stone-lifting contest? Well, now he’s Mr. Universe, and he’s at Stachus square in his underwear.” The papers thought it an amusing story and picked it up (p. 68).

It is often said that you should work on your fortes rather than combating your weaknesses. Schwarzenegger has always done both. It is another thing he learned in bodybuilding. Like all people, he had muscles that responded very quickly to the training (including his biceps or his chest) and others that gave him a hard time, such as his calves. “The challenge,” Schwarzenegger writes, “was to take the curse off all those weak points. It’s human nature to work on the things that we are good at. If you have big biceps, you want to do an endless number of curls because it’s so satisfying to see this major biceps flex. To be successful, however, you must be brutal with yourself and focus on the flaws. That’s when your eye, your honesty, and your ability to listen to others come in. Bodybuilders who are blind to themselves or deaf to others usually fall behind” (p. 93). While other bodybuilders at the studio loved to flaunt their strong muscle groups, he did the exact opposite: “When I got to California, I made a point of cutting off all my sweatpants at the knees. I would keep my strongpoints covered – my biceps, my chest, my thighs – but I made sure that my calves were exposed so everyone could see” (p. 94). The other bodybuilders did not see the point in exposing your weak spots, but for Schwarzenegger their condescending looks meant additional incentive to step up his workout regiment.

Moreover, Schwarzenegger was neither afraid to make mistakes, nor did he have any problem admitting to them. It is precisely because he keeps talking as openly about his errors and misguided decisions as he talks about his achievements that makes his autobiography such a good and convincing read. By the way, his real estate investments were flops before they became extremely successful, as he admits on pages 121-22.

Schwarzenegger also stresses that he would never have become as successful if he had not put down his goals in writing. “I always wrote down my goals, like I’d learned to do in the weight-lifting club back in Graz. It wasn’t sufficient just to tell myself something like ‘My New Year’s resolution is to lose twenty pounds and learn better English and read a little bit more.’ No. That was only a start. Now I had to make it very specific so that all those fine intentions were not just floating around. I would take out index cards and write that I was going to:

- get twelve more units in college;

- earn enough money to save $ 5,000;

- work out five hours a day;

- gain seven pounds of solid muscle weight; and

- find an apartment building to buy and move into.

It might seem like I was handcuffing myself by setting such specific goals, but it was actually just the opposite: I found it liberating. Knowing exactly where I wanted to end up freed me totally to improvise how to get there” (pp. 137-38).

Schwarzenegger also stressed how important it is to set very big goals for yourself: “People were always talking about how few performers there are at the top of the ladder, but I was always convinced there was room for one more. I felt that, because there was so little room, people got intimidated and felt more comfortable staying on the bottom of the ladder. But, in fact, the more people that think that, the more crowded the bottom of the ladder becomes! Don’t go where it’s crowded. Go where it’s empty. Even though it’s harder to get there, that’s where you belong and where there’s less competition” (pp. 298-99).

He was uncompromising when it came to achieving his goals, and he ignored some seemingly sound and lucrative opportunities whenever he felt they did not help him achieve his fixed objectives: “Nothing was going to distract me from my goal. No offer, no relationship, nothing” (p. 142).

Schwarzenegger was always a good observer who detected opportunities where no one else would see them. When he first came to the United States, he made his money working in construction on the side. Yet he soon realised where the value-added was in this business. “Many of our jobs entailed fixing up old houses, and it was eye opening. The owners would pay us $ 10,000 to fix up a house they’d bought for $ 200,000. Then they’d turn around and sell it for $ 300,000. Clearly there was real money to me made. So I put aside as much money as I could and started looking around for investment possibilities” (p. 148).

The average American tends to buy a single-family home, but Schwarzenegger always went against the grain: “I wanted an investment that would earn money, so that I could cover the mortgage through rents instead of having to pay it myself. Most people would by a house if they could afford it; it was very unusual then to buy a rental property. I liked the idea of owning an apartment building. I could picture starting with a small building, taking the best unit for myself to live in, and paying all the expenses by renting out the rest” (p. 148). For a young immigrant in his early twenties, it was certainly not the standard approach to take.

Schwarzenegger spent the next several years conducting systematic real estate research: “I knew every building in town. I knew every transaction: who was selling, at what price, how much the property hat appreciated since it last changed hands, what the financial sheet looked like, the cost of yearly upkeep, the interest rate on the financing. I met landlords and bankers” (p. 149). Eventually, he found an apartment building that cost him $215,000. He invested his entire savings ($27,000) and borrowed another $10,000 from his promoter Joe Weider. Many advised him against the investment, but Schwarzenegger has always been someone who prefers making a decision on the basis of possibly insufficient facts, rather than finding well-informed reasons for inaction. After all: “Often it’s easier to make a decision when you don’t know as much, because then you can’t overthink. If you know too much, it can freeze you. The whole deal looks like a minefield” (p. 150).

Three years later, by the way, he sold his first apartment building for four times the amount. “The profit on my $37,000 investment was $150,000 – I’d quadrupled my money in three years. I rolled the whole amount into a building twice the size, with twelve apartments rather than six… Making money this way doubled my confidence. I adjusted my life plan. I still wanted to own a gymnasium chain eventually, but instead of making money from movies, like Reg Park and Steve Reeves did, I would make it from real estate” (pp. 215-17).

But let’s get back to bodybuilding where he initially made his money, turning himself into a brand: At the time, it was anything but a popularly known sport, and had a rather dubious image. People believed this kind of sport (with most not even considering it a sport) was pursued only by extreme narcissists or else by individuals with a full-blown inferiority complex (p. 151). Schwarzenegger set himself the task of popularising bodybuilding and to rid of its niche sport image. “I was still focused on wanting to see bodybuilding go mainstream. It frustrated me that bodybuilding shows were never advertised to the general public” (p. 159). He started to organise larger bodybuilding contests in his own right, and one of his major achievements was certainly to popularise bodybuilding and fitness in the United States and around the world and to end its niche existence.

At the same time, he began to work on his acting career. The comments he received concerning his changes in this line of business were almost universally negative. Acting experts told him: “Look, you have an accent that scares people … You have a body that’s too big for movies. You have a name that wouldn’t even fit on a movie poster. Everything about you is too strange.” Yet a female friend had this advice regarding Hollywood for him: “Just remember, when they say ‘No’ you hear ‘Yes’, and act accordingly. Someone says to you; ‘We can’t do this movie,’, you hug him and say, ‘Thank you for believing in me.’” (p. 168).

For him, acting meant primarily finding access his emotional side, to his feelings – and to talk about them and to reflect. It was a new, surprising and exciting experience for him. “It was the first time I’d heard anybody articulate ideas about the emotions: intimidation, inferiority, superiority, embarrassment, encouragement, comfort, discomfort. A whole new world of language appeared … It was broadening my horizons to things that I’d ignored. In competition, I’d always walled off emotions. You have to keep your feelings under control or you can be knocked offtrack. Women always talked about emotions, but I considered it silly talk. It did not fit into my plan” (p. 177). Now the time had come for him to open the door on his emotions. And initially it was not an easy thing to do. His acting coach told him: „You sell yourself as being the kind of guy who doesn’t experience emotion, but don’t delude yourself. Not paying attention to it or dismissing it doesn’t mean that it is not part of you. You actually have the emotions because I see it in your eyes when you say certain things” p. 178).

Schwarzenegger also got into Transcendental Meditation, a consciousness-developing technique quite in vogue in California at the time, because it seemed perfectly plausible to him that your mind or sub-conscious needs training every bit as much as your muscles do (p. 182).

Having been the No. 1 in bodybuilding and having enjoyed a high degree of recognition, it was not easy for him to start from scratch in acting and to find himself at the receiving end of much criticism. But it was exactly what tickled him – for he needed a new challenge, unwilling to rest on his laurels. Initially, it was hard for him to handle this unfamiliar situation. One acting coach warned him that this career shift would imply a huge challenge for him: “In this world, I wasn’t number one in the universe; I was just another aspiring actor. He was right. I had to surrender my pride and tell myself, ‘Okay, you’re starting again. You’re nothing here. You’re just a beginner. You’re just a little punk around these other actors” (p. 185).

The secret of Schwarzenegger’s success was his extreme eagerness to learn paired with his ability to learn. He hired coaches for everything he tackled. For instance, he took a language coach specializing in accents in order to reduce his accent (p. 193). And he always made a pinpoint effort to make the acquaintance of successful personalities in order to learn from them directly: „When I wanted to know more about business and politics, I used the same approach I did when I wanted to learn about acting: I got to know as many people as I could who were really good at it” (p. 291).

While he learned, on the one hand, to master the rules of acting (and, later on, of politics) it always gave him pleasure to break the rules and to swim against the current – in fact, it was one of the preconditions for positioning himself as a brand. His idol in this respect was Muhammad Ali. “What separated him from other heavyweights wasn’t only his boxing genius – the rope-a-dope, the float like a butterfly, sting like a bee – but that he went his own way, becoming a Muslim, changing his name, sacrificing his championship title by refusing military service. Ali was always willing to say and do memorable and outrageous things” (pp. 194-95). When Schwarzenegger met the mother of his wife-to-be for the first time, the highly respected Eunice Kennedy Shriver, the first thing he told her about her daughter was: “Your daughter has a great ass” (p. 222).

Schwarzenegger also had an innate tendency to represent controversial opinions and to provoke people, though he does emphasize: “But outrageousness means nothing unless you have the substance to back it up – you can’t get away with it if you’re a loser” (p. 195). What he had yet to learn was the art of portioning his provocative remarks correctly – not too much, and not too little of it, breaking with convention but stopping short of being eccentric. Initially, he occasionally overstepped the mark and said things about himself that would hurt him later on and that should have been left unsaid. “I still didn’t know the difference between outlandish and offensive” (p. 195).

Time and again, Schwarzenegger stresses the significance of PR in his autobiography, showing a high-level sensitivity for the way PR works. Even in his days as a bodybuilder, he took an interest in the subject. He mentions one adviser who told him “that ordinary press releases were a waste of time, especially if you were trying to get the attention of TV reporters. ‘They don’t read!’ he said. Instead, he knew dozens of journalists and their editors personally” (p. 204).

Schwarzenegger’s book makes repeated mention of the fact that he kept urging film distributors to do more for international PR. Even for his first picture, Pumping Iron, he made a much greater marketing effort than other actors did – and did so not just to promote the film but also and above all because he saw it as an opportunity to market himself as a person: “I was also promoting myself. Every time I was on the radio or TV, people became a little more familiar with my accent, the Arnold way of talking, and a little more comfortable and at ease with me. The effect was the opposite of what the Hollywood agents had warned. I was making my size, accent and funny name into assets instead of peculiarities that put people off” (p. 213-14).

On occasion of his first major film hit, “Conan the Barbarian,” the film studio suggested he do some promotion in Italy and France. From his point of view, this was laughably insufficient. So he said: “Guys, why don’t we be more systematic? Spend two days in Paris, two days in London, two days in Madrid, two days in Rome, and then go up north. Then say that we go to Copenhagen, and then to Stockholm, and then to Berlin. What’s wrong with that?” (p. 278).

He did another extremely ambitious PR tour for the sequel, “Conan the Destroyer”: “I went on as many national and local talk shows as would book me, starting with Late Night with David Letterman, and gave interviews to reporters from the biggest to the smallest magazines and newspapers.”

Schwarzenegger underscores the fact that his attitude toward PR differed radically from that of other actors and authors who saw themselves primarily as artists and felt it was beneath their station to sell themselves. “The typical attitude seemed to be, ‘I don’t want to be a whore. I create; I don’t want to shill. I’m not into the money thing at all.” Schwarzenegger, by contrast, had a far more affirmative attitude toward making money, and considered himself primarily a business man: “Too many actors, writers, and artists think that marketing is beneath them. But no matter what you do in life, selling is part of it” (p. 279). Again and again, he emphasises in his book: “Same with bodybuilding, same with politics – no matter what I did in life, I was aware that you had to sell it” (p. 342).

Unlike many other Americans, Schwarzenegger never limited his vision to the United States, but early on made the whole world his stage. Both with a view to his films and in regard to his books, he argued: “The United States accounts for only 5 percent of the world’s population, so why would you ignore the other 95 percent? Both industries (films and books, R.Z.) were shortchanging themselves” (p. 279).

“Whenever I finished filming a movie”, Schwarzenegger writes, “I felt my job was only half done. Every film had to be nurtured in the marketplace. You can have the greatest movie in the world, but if you don’t get it out there, if people don’t know about it, you have nothing. It’s the same with poetry, with painting, with writing, with inventions” (pp. 341-42).

Thinking in global terms is a characteristic of Schwarzenegger that sets him apart from many other Americans. With each film he starred in, he wondered how it might be received in other countries. “How will this play in Germany?, Will they get in Japan? How will this play in Canada? How will this play in Spain? How about the Middle East?” Most of his film, according to Schwarzenegger, actually did better outside the United States. “That was partly because I traveled all over promoting them like mad” (p. 340).

All things considered, Schwarzenegger’s life is marked by a tremendous intensity and diversity, and this becomes obvious in each and every chapter in the book. “I loved the variety in my life. One day I’d be in a meeting about developing an office building or a shopping center, trying to maximize the space. What would we need to get the permits? What were the politics of the project? The next day I’d be talking to the publisher of my latest book about what photos needed to be in. Next I’d be working with Joe Weider on a cover story. Then I’d be in meetings about a movie. Or I’d be in Austria talking politics with Fredi Gerstl and his friends. Everything I did could have been my hobby. It was my hobby in a way. My definition of living is to have excitement always; that’s the difference between living and existing” (p. 291).

In acting, he was initially enthralled by action films. Serialised films such as Conan or Terminator where certainly big box-office hits, but eventually Schwarzenegger sought recognition in perfectly “normal” films, too. He discovered early in the game that humour was his very own trademark, especially when compared to other action heroes such as Sylvester Stallone, Clint Eastwood or Chuck Norris (p. 338). Indeed, his dead-pan one-liners became the trademark of his films in general. “From then on, in all my action movies, we would ask the writers to add humor, even if it was just two or three lines. Sometimes a writer would be hired specifically for that purpose. Those one-liners became my trademark” (p. 340).

The next goal that Schwarzenegger set for himself was to star in comedies and to make a success of it. Nothing says more about his success recipe and his approach to life than the fact that he actually enrolled in a study program on humour and hired a mentor to coach him. Who else would come up with the idea of learning how to be humorous systematically and to hire a comedy coach? “You have to figure out your potential. So let’s say on a scale of 1 to 10, with Milton Berle a 10, my potential is a 5. In comedy his potential was much greater than mine, obviously, but maybe not in something else … But the trick is how do you reach 100 percent of your potential? It was the right time in my career to expand into comedy and throw everything off a little bit” (p. 358). He adds that for him as European it was particularly difficult because Americans simply have a different sense of humour than Europeans.

At the same time, Schwarzenegger began to mingle with top-notch comedy actors and to immerse himself in their scene. “So meeting these guys and being included in their world gave me a chance to understand it (the American sense of humour, R.Z.) better. I discovered that I really like being around people who are funny and who write comedy and who are always looking to say things in a unique way” (pp. 358-59).

The first pure comedy that Schwarzenegger starred in became a huge financial success for him – because rather than negotiating a fixed fee, he had agreed to a cut of the profits, which proved very lucrative. The idea was inspired by the realisation that a normal fixed fee for three very successful Hollywood actors would be too expensive to make the film production profitable for the studio. So Schwarzenegger and the two other stars signed a deal that would pay them 37.5 percent each of the revenues. “And that 37.5 percent was real, not subject to all the watering-down and bullshit tricks that movie accounting is famous for” (p. 363). As it turned out, the arrangement for this film alone earned him more than $35 million (p. 374).

With Schwarzenegger having achieved the highest level both in bodybuilding and on the silver screen, he looked around for the next challenge. “Becoming the biggest action star had been the next challenge. Eventually I’d accomplished that as well. Then I’d gone another step, into comedies. But I’d always known I’d grow out of that too … I loved the idea of new challenges, along with new dangers of failure” (pp. 402-3). The next challenge he rose to was politics.

Schwarzenegger’s political instincts were those of a Republican, as he writes. He admired Richard Nixon and particularly Ronald Reagan because they represented the freedom of the individual and the superiority of free market economics versus state interventionism. This basic conviction has remained a constant in his thinking throughout his life. The thinker he admired most was economist Milton Friedman. In this respect, he represented the typical Republican.

In other respects, however, he used to, and continues to, represent beliefs that are rather Democrat – for instance when it comes to issues such as abortion, same-sex marriage, climate change and environmental protection and “gun rights.” Schwarzenegger was politically socialised through the Kennedy clan, and the fact is reflected in many of his political views. After all, having married into the Kennedy family, his in-laws were obvious role models, despite many political differences. It therefore comes as no surprise when Schwarzenegger more than once notes in his autobiography that his own party has regretfully drifted too far toward the right during the Bush administration.

The opportunity to hold a high political office presented itself in the context of a so-called “recall” process that was initiated against the incumbent Governor of California. Schwarzenegger narrates how he hesitated until it was almost too late before he decided to run for the office, not least because his wife vehemently opposed it (pp. 494+). Eventually he announced his candidacy unexpectedly at a talk show. His maxims during the election campaign read: “Don’t get caught up in detail. Be likeable, be humorous. Let the others hang themselves. Lure them into saying stupid things” (p. 509).

During his campaign, he was savagely attacked by his opponents: Women accused him of sexual harassment; his father was dubbed a “Nazi,” and he himself was suspected of admiring Hitler. How did Schwarzenegger respond in this situation; how did he parry the attacks? “My rule of thumb about damaging accusations was that if the accusation was false, fight vigorously to have it withdrawn; if the accusation was true, acknowledge it and, when appropriate, apologize” (p. 511).

The stories about his alleged admiration for Hitler were easy to defuse for him, and as far as sexual harassment went, to told a broad audience: “A lot of those stories are not true. But at the same time, I always say wherever there is smoke, there is fire. And so, yes, I have behaved badly sometimes. Yes, it is true that I was on rowdy movie sets, and I have done things that were not right, which I thought then was playful, but now I recognize that I have offended people. And those people that I have offended, I want to say them, I am deeply sorry about that, and I apologize” (p. 511).

This, by the way, is an excellent example for the rhetoric of someone like Arnold Schwarzenegger. He picks up in something that most people are thinking anyway (“wherever there is smoke, there is fire”), rejects the allegations, and simultaneously apologizes to everyone across the board whom he may have caused grief. The way he attacked his opponents during the campaign once again highlighted his gift for public relations.

Accordingly Schwarzenegger won his first campaign by a wide margin – but his troubles were only just beginning. Then as now, California suffered from an extremely high debt level. Schwarzenegger found it hard to get on top of the situation – as anybody else would have, too – because many interest groups representing the public service had successfully bargained for extremely high pension agreements, including annual raises. Moreover, he regularly had to take on the powerful unions.

He sometimes prevailed because he kept resorting to instruments of grass-root politics and submitted his reform proposals in the form of referendums. Occasionally it sufficed for him to merely threaten another proposition. In the end, however, he proved unable to break the power of unions and interest groups.

At the end of his first term in office, he was lagging far behind in the polls and most people thought his chances for a second term were slim. But once again, Schwarzenegger proved to be extremely flexible and willing to learn, as he approached his opponents, sought political compromises where in the past he would have opted – often futilely – for confrontation. The financial and home price crisis that hit California particularly hard during his second term kept him from resolving the huge deficit problem that burdened California. In the end, however, he had every reason to look back with pride at his track record: „We made a hell of a lot of progress, and we made a lot of history: workers’ comp reforms, parole reforms, pension reforms, education reforms, welfare reforms, and budget reforms not once, not twice, but four times… We made our state an international leader in climate change and renewable energy; a national leader in health care reform and the fight against obesity; we launched the biggest infrastructure investment effort in generations; and tackled water, the thorniest issue in California politics” (p. 587).

At the end of his book, he offers a number of tips, and tries to identify the factors that were definitive for his enormous success. In particular, he stresses the importance of daring to be different and to take exception. His advice is to stay away from the mainstream. “Never follow the crowd. Go where it’s empty” (p. 605). Above all, one should never take “No” for an answer. “When someone tells you no, you should hear yes… The only way to make the possible possible is to try the impossible” (p. 605). Finally, he keeps emphasizing how important it is to be a “good seller.” “No matter what you do in life, selling is part of it… People can be great poets, great writers, geniuses in the lab. But you can do the finest work and if people don’t know, you have nothing!” (p. 606).

His last piece of advice is: “Don’t overthink.” Those who spent too much time analysing everything instead of acting will fail in life. He adds that in some ways you have to learn to trust your instincts. And finally, humour is what often helps to convince people, to succeed – and above all to enjoy life. The books ends with the appeal: “We should all stay hungry!” (p. 618). What this might mean for Arnold Schwarzenegger himself, who is now 65 years old, is anybody’s guess. No matter what, though, it will exciting to see what his plans are, and what the next stops in his life will be. R.Z.